The Queens in the hands of Gian Carlo Guerra

When Scaglietti started working for Enzo Ferrari, Guerra – who was by that point an extremely skilled panel beater – became the workshop’s flagship.

Ferrari appreciated him and Scaglietti often used him as a shield: with him, Drake’s rages were more easily placated. According to Ferrari, Guerra is “Carlo Rizzulein” (the curly one): he spoke with him in Modena dialect and he rarely got angry with him.

– I had to wait for the Knight Commander every evening, as he came to check on the advancement of the jobs. I was a friend of his son, Dino, who often came to the workshop and stopped for a chat. Even when he started feeling ill, he arrived, he sat next to me and I tried to involve him. When I did something which Ferrari didn’t want me to do, I discussed it with him first. For example, once I told him: “Dino, I thought about doing one thing that I know full well your father won’t like”, it was a headrest, something which everybody had by that time. Actually, engineer Fraschetti had passed away: if he’d had a headrest, I’m convinced that he would have made it. I mean, I decided to do as I wanted to and I got to work, adding other changes to the car too. Ferrari’s reaction wasn’t one of the best. He stormed in noisily opening the glass door and saying: “Why did you do it? I don’t like it!”. “I did it as it was something useful. And it’s also nice.” I answered. And he answered: “That’s not a good reason!” That was one of the few times that we had an argument.

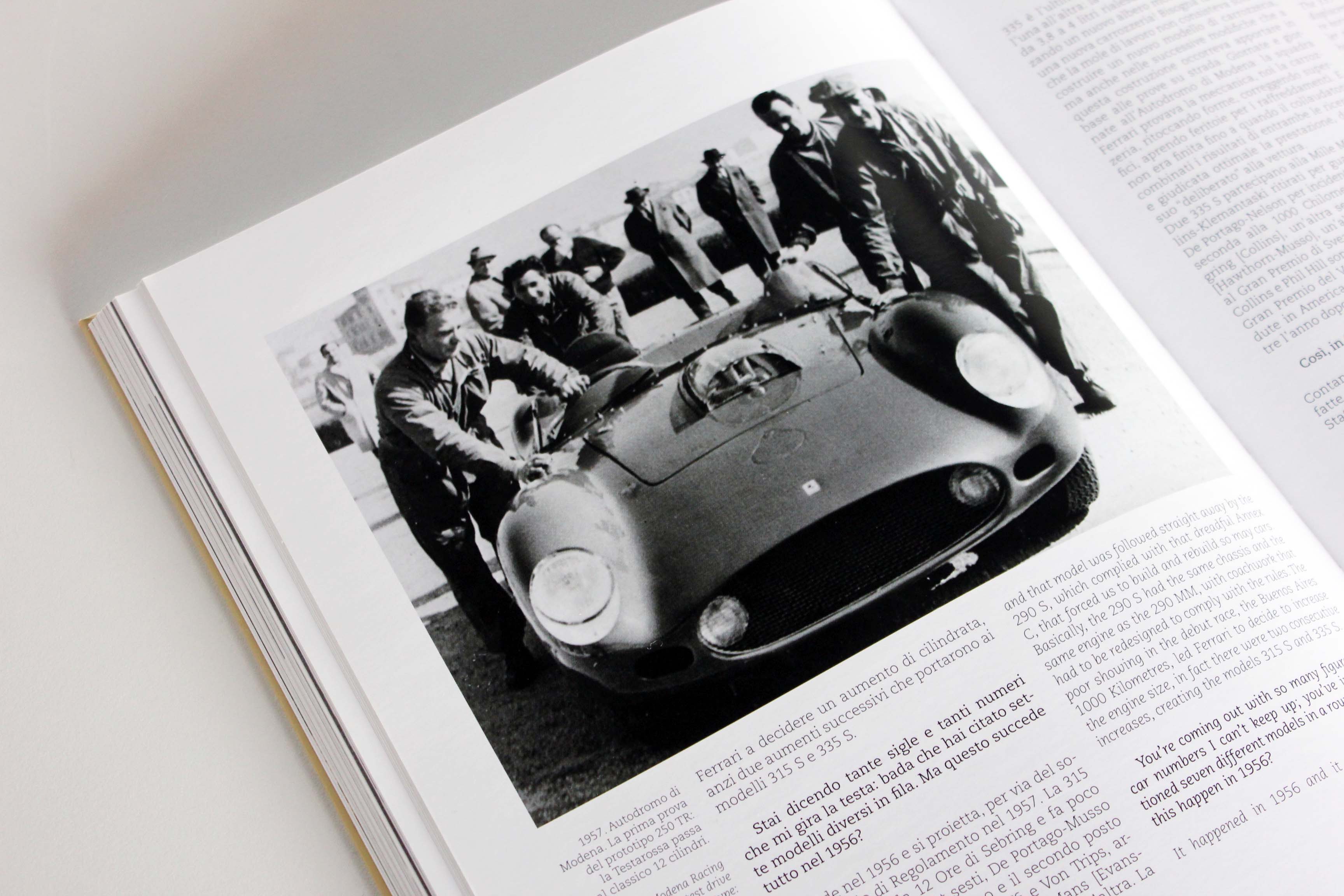

- Pic of the volume “L’ê andéda acsè” written by Franco Gozzi, Artioli Editore

– Earlier on, you were mentioning how you made the 250 TR and other cars, like the 500 Mondial: “drawing” it with a steel thread. How did it work: had you already drafted the drawing on paper? Did you have it in your mind?

– No, even with the Mondial I did it like this… I observed the dummy with the tanks, the bulk of the mechanics and of the suspensions. Afterwards, I got the 6mm calipered thread and I pulled it like this, from front to rear, with a guy in it for the driver’s size. Then I did the sides and the rest. At the end, it was the time for the metal panels.

It was about having the right awareness to build and handle that material searching for lightness, in order to compete with the competition. You worked based on sensations, applying experience gained from the previous car.

- Pic by Tommaso Ferrari

– Therefore, the drawing on paper was only made after you had drawn it with the thread?

– No, it wasn’t done at all.

– Scaglietti didn’t draw it either?

– No. The starting points were the dummies, which were initially made in wood and then in the metal alloy.

– Okay, no drawing then. And which tools did you use to beat the metal? Did you use the hammer and the sack of sand, just like it was done traditionally?

– When I arrived at Scaglietti’s, they used some mallets this long and some wooden blocks, which were too stiff. You made a whole and you beat the metal like that. It’s only that this mechanism didn’t work: by beating a portion, the other side came up. So, one day, I went to see the upholsterer and I asked them to create a bag with the truck’s fabric. Then, we created very useful pillows with that bag. Each one of us, panel beaters, adapted their working tools to their own characteristics: those who used their wrist made shorter hammers, those who used their elbow had longer hammers.

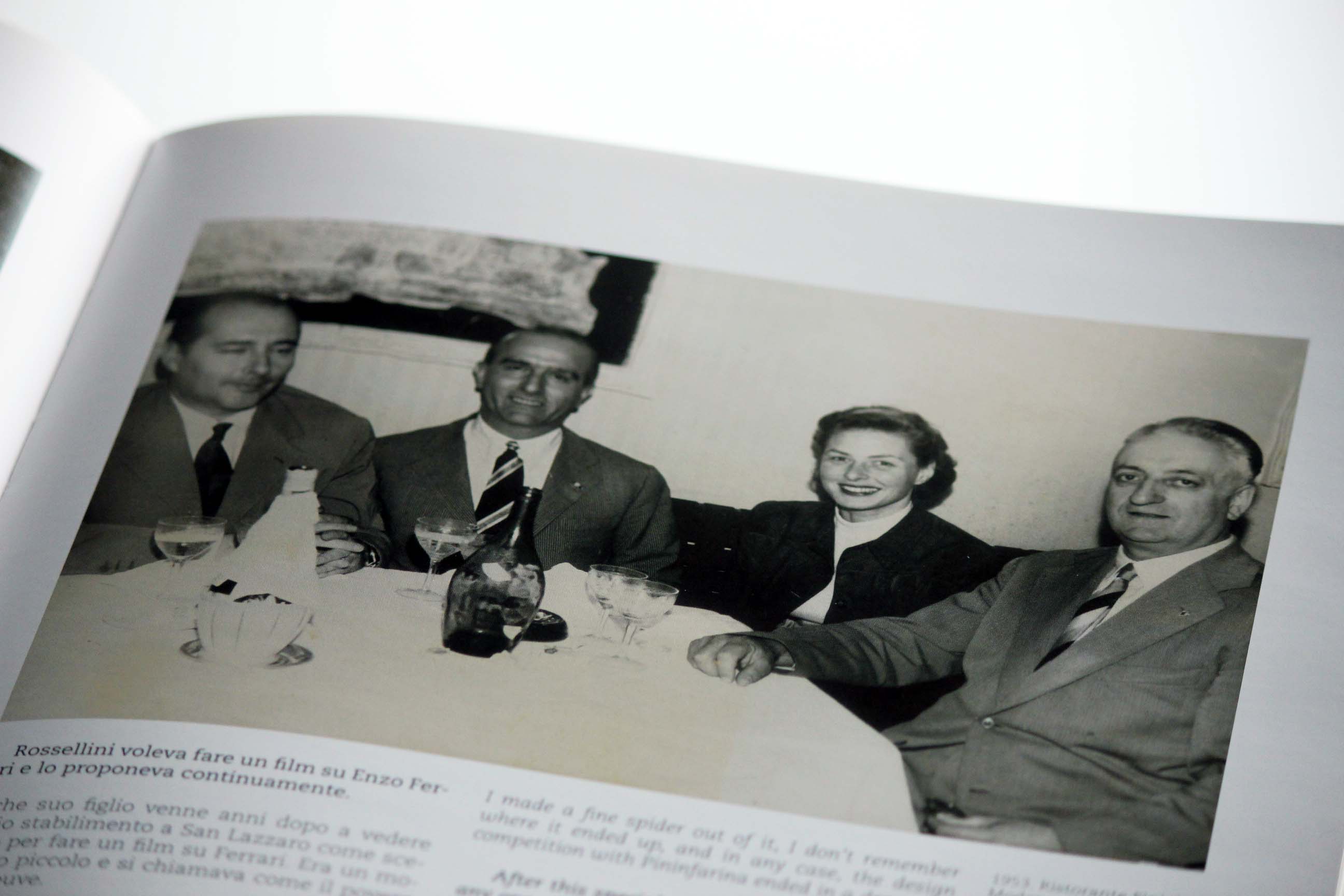

Guerra speaks softly. He has a feeble voice and he smiles often. He goes over his memories mentally and he talks as if he was actually browsing through them: smiling at the many pictures of someone who has gone through his life. He also met Roberto Rossellini. He worked on the Ferrari 375 that the film director drove up and down Italy, using it as if it was a normal car. Actually, at the time, Rossellini already had it in mind to make a film about Enzo Ferrari: a masterpiece which has never come to light, which should have included also the Scaglietti plant in San Lazzaro, amongst other locations. Guerra files the memory with a smile. “Rossellini was a good man. Ingrid Bergmann was also with him: a beautiful lady”.

- Pic of the volume “L’ê andéda acsè” written by Franco Gozzi, Artioli Editore

Then he goes through the long list of the drivers that he met: Musso, Phil Hill, Peter Collins, Ascari, Villoresi… his favourite was always Juan Manuel Fangio.

– Yes, I loved Fangio even if he made me “struggle” because he was demanding: he wanted many things that we didn’t actually do. For example: once I made a windscreen especially for him. When he went to the mountains, he told me that the air got on his helmet and it caused him a headache. So I made him a windscreen with a rectangular Plexiglas piece, surrounded by an iron frame, two small hooks which I had soldered on and then some levers which enabled you to pull the windscreen down. When Fangio saw it, he went crazy!

– Did you go to the tracks with the drivers?

– No, I never went to the tracks. I knew them well though, I was everybody’s friend and even if sometimes they came with certain requests… Ferrari always said it: “drivers don’t make cars, they break them.”

– And as you liked making cars, did you also like driving them?

– I didn’t drive cars much. I don’t have classic Ferrari’s nor Lamborghini’s.

– Talking about Lamborghini… you started working for Scaglietti when you were 22 and you stayed there for a long time. Then your season with Lamborghini started.

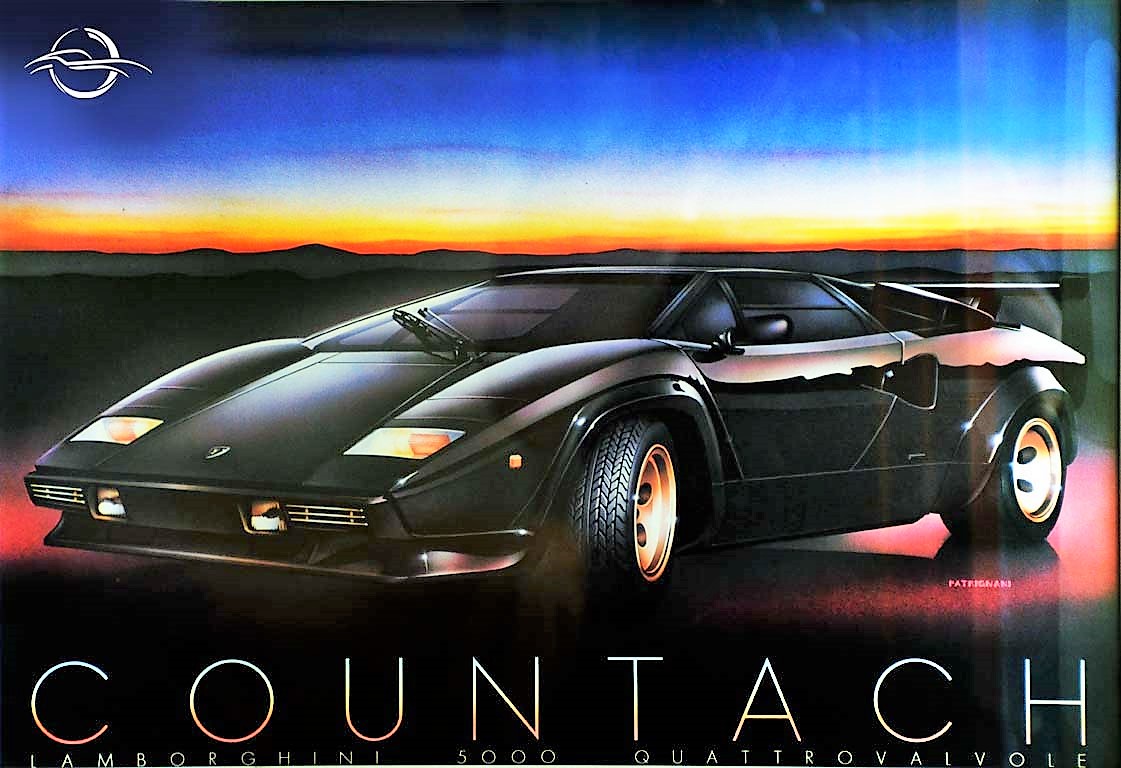

– Yes, I have to make a confession, I am more attached to Lamborghini, that isn’t due to Ferrari, who told me “Do as you please!”, but due to the new Fiat executives who ruled, or wanted to rule. I was called to the bull’s company to make the Countach. I was contacted by engineer Stanzani and this is how it went: we met in a tavern near Nonantola and the engineer asked me if I could put my hands on the car, which in Turin had been judged as impossible to make. It was low, very low! The test driver was Bob Wallace, who was ‘mad’. He told me: “I made this seat!” And I answered: “But this isn’t a seat: it’s a dog’s kennel!” That is how it all started.

- Pic by Tommaso Ferrari

– Did you meet Ferruccio Lamborghini?

– Sure. Once he came as there was a strike and he asked where he could find Stanzani. However, first he came to see me and he asked me: “Who’s that engineer who made me the Countach?”. I answered: “Mr Ferruccio, I’m not an engineer, but I made you the Countach anyway”… In the end, that year, I made 114 of them!

Another project which Mr Guerra participated in is Cizeta. What can you tell us about the carbon fibre spoiler? “Claudio Zampolli didn’t want it as he said that it would have been too ventured and sporty, while I said that it needed something on the back, to make it more visible”.

- Pic by Tommaso Ferrari

A lot of water has passed under the bridge since Guerra – who was a little older than a child – dreamt of being a footballer and worked as an assistant for Campana. Today I have an elderly Master in front of me: one of those who trained generations of panel beaters.

Guerra remembers Afro Gibellini and Egidio Brandoli, the two who were the best, according to him.

– Sometimes, I even kicked my trainees in the backside… but none of them ever got upset. For me, they were all the same and they all still love me.

His eyes shine. His wife simulates a reproachful look, but you can tell that she’s actually laughing to herself. “That’s nice! I also had some female workers, but I never kicked them in their backside”, she approaches her husband. This is the least Hollywood-style couple that I ever met, and it’s also one of the nicest. Within these four walls, permeated with memories, you breathe a complicity which is rare to find in a couple in their eighties. To the extent that I spontaneously ask her, Maria, how they met.

– Gian Carlo was a friend of my brother. One day, he asked his permission to take me to a party and that is when it all started. At the time, he also used to sing in the dancehalls we used to attend.

–Did he sing well?

Maria shrugs. She sits next to him quietly, just like she’s been doing for over sixty years.

- Pic by Tommaso Ferrari

Guerra smiles and, while I take my leave, centuries of art’s history flow in front of my eyes. I think back to the old “artist’s shops”, the names which have never emerged to the footlights, the generations of the “anonymous” who – as a rule – never signed the works that they created. An army of unknown geniuses that history has ruthlessly passed on to oblivion. But this doesn’t seem to matter to Guerra. It’s the logic of things, which he gives in to with indulgency. With an old patience. It’s the secret awareness that many, even in the future, will continue to call him Master.

By International Classic, written by Martina Fragale

Read also:

Ferrari and Lamborghini – Chapter 1